The St. Clair River is a world-class fishing and boating destination, and home to a rich diversity of wildlife. But over the last century, the 44-mile stretch of river has been the site of exponential human activity.

People have bored pipelines bored into and out of it, added seawalls along its banks and dredged channels into its riverbed. These changes maximize the waterway’s usefulness, but create challenges for the fish, amphibians, insects, birds and mammals that also call the area home.

“Development along the St. Clair River wasn’t always made with wildlife in mind, but fortunately great work is being taken to remedy these issues,” said Matt Pedigo, chair of the Michigan Wildlife Council. “The St. Clair River is a crucial part of one of the largest freshwater reserves in the world, and improving any part of the Great Lakes improves the overall ecosystem. Healthy wildlife means healthy natural resources, and vice versa.”

The goal of the Michigan Wildlife Council is to highlight the critical role that wildlife management plays in the conservation of the state’s natural resources. In Michigan, the management of the state’s wildlife and natural resources is primarily funded through the purchase of hunting and fishing licenses and equipment – not state taxes.

“A lot of times, the work has long lead times, meaning we won’t necessarily see the benefits for years, but the St. Clair River is seeing immediate results,” Pedigo said. “Species like mudpuppies and sturgeon have already started making their way back into the area in numbers that are astonishing even the experts.”

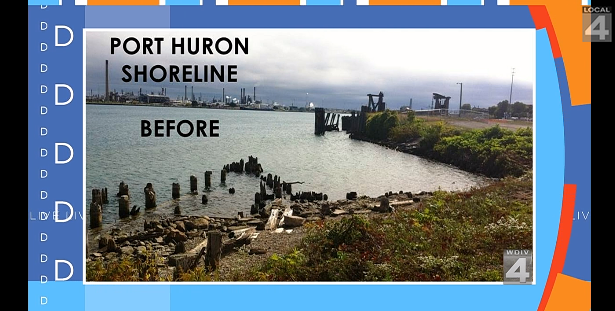

In 1987, the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement designated the St. Clair River as an area of concern, citing 10 fixable environmental impairments. Among them were the river’s sediment and water qualities, which were declared contaminated due to the activity of nearby factories, golf courses and human habitation. Additionally, the hardened shorelines made breeding difficult for wildlife such as frogs and turtles that depended on soft riverbanks, and it was discovered that the channels that had been dredged in the middle of the river to accommodate commercial shipping discouraged fish like pike from living there. In 2011, a Wildlife Action Plan was put into effect, and seven years later, life along the river is teeming again.

“The enhancements made to the St. Clair River over the last decade have been the most impressive improvements I’ve seen in my 32 years working for the government,” said Rose Ellison of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Great Lakes National Program Office. “With these changes, it’s possible for both humans and animals to live and work in close proximity again.”

Michigan’s Wildlife Action Plan is part of a national conservation strategy developed to protect wildlife and ecosystems. The Michigan version was specially developed by conservation partners across the state, including the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality’s Melanie Foose, who served as the plan’s area of concern coordinator.

“Of the 10 environmental impairments originally present, only two remain,” she said. “We know we’ll never get the river back to its condition before people settled here, but we wanted to re-create as many habitat types as possible that have been lost over the years.”

Some of the work that was done included removing seawalls to allow amphibians and reptiles to enter and exit the waterway safely. In-river projects were also developed, including submerging logs and rocks for use by fish and aquatic macroinvertebrates (insects, arthropods and worms) as hiding and breeding areas.

“We also spent a lot of time improving tributaries around the river so that Great Lakes fish could get farther inland,” Foose said. “After the first year, we found a pregnant pike 3,000 feet from the river in an area where, previously, she wouldn’t have been able to get more than 400 feet. There are no words to describe how exciting that was.”

In addition, extensive work was done to develop the shorelines, including planting flowering plants that encouraged pollinators such as bees and butterflies to return to the area. Other species that have been spotted include red-backed salamanders, snakes and toads, as well as some larger mammals, including mink and beavers. Folks who want to get an up-close-and-personal look at these improvements have a wide variety of vantage points to choose from, including the Blue Water River Walk in Port Huron or Algonac State Park near where the river empties into Lake St. Clair. Views from the water can also provide an inimitable view.

“Boating season starts next week, with a lot of the public docks opening on April 1, so that’s a great time to get out,” Pedigo said. “This area is teeming with life, and it’s great to know that thanks to the work that’s been done, it will be able to be enjoyed for generations to come.”