In a state chock-full of natural wonders, the St. Clair-Detroit River system is one of the most distinctive, referred to by one conservationist as Michigan’s “sparkling gem.” The unique waterway linking Lake Huron to Lake Erie is considered North America’s largest freshwater delta, and the varied habitats of this system make for a biodiversity hotspot, supporting 65 types of fish and dozens of amphibian, reptile, mammal and mussel species, as well as serving as an important breeding area for 200 migratory bird species.

“The St. Clair-Detroit River system is a wonderful place for people to recreate on and live near, therefore we have an obligation to do all we can to successfully live together with the rare, diverse set of critters that also call that region home,” said Amy Derosier, coordinator of the Wildlife Action Plan. “Michigan is about water, and this system is the state’s sparkling gem. When you think of what makes the Great Lakes great, this is part of it.”

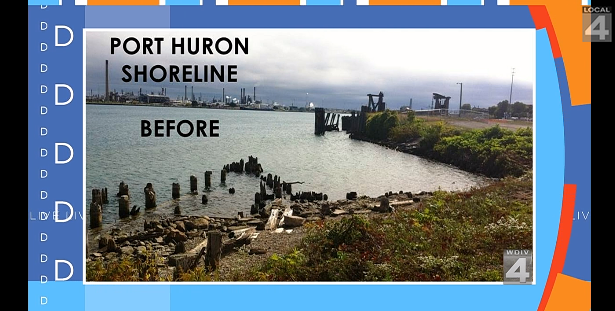

Years of nearby urban sprawl have compromised the ability of some of these species to thrive, generating concern among environmentalists. That’s why the water system – consisting of the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River – received its own breakout section in the most recent Michigan’s Wildlife Action Plan. The St. Clair-Detroit River system aspect is one of 15 chapters, or “mini-plans.” Taken together, the plan provides a road map toward helping species in greatest conservation need, outlining priorities for the next 10 years.

The St. Clair-Detroit River mini-plan focuses on four fish species – northern madtom, mooneye, pugnose minnow and lake sturgeon – and one amphibian – mudpuppy – that each represent a unique aspect of the system. The madtom, for instance, is a bottom-feeding catfish that has seen its numbers drop as the riverbeds were dredged to accommodate shipping traffic. Similarly, mudpuppies have suffered as over the years natural earthen shorelines have been replaced with concrete and seawalls, making it difficult for the salamander species to breed.

“These are smaller things that are happening in the system that could have bigger effects, and these species are the first to show us that something needs to change,” Derosier said. “It could mean we’re losing water quality or permanently altering key parts of our environment – parts that we depend on as well.”

Derosier points to the fact that this area is also home to floodplain forests, wetlands and managed wetlands, which are all helpful at absorbing floodwaters. If those disappear, she said, it could impact houses and businesses all through the watershed, from Port Huron to Monroe. But flooding isn’t the only way that activity in this system could affect humans. It is a destination for Michiganders of all ages, providing a multitude of outdoor recreational opportunities, including fishing, bird watching, hunting, swimming and boating. It’s also a major source of drinking water.

“This is a quality-of-life issue,” said Scott Hanshue, senior fisheries management biologist for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. “Millions of Michigan residents rely on the St. Clair and Detroit rivers for their drinking water. The system has been disturbed since we colonized North America, but it still supports a high diversity of fish and wildlife. To put it in perspective, this is where dollars need to go to maintain quality.”

And because this system is vital for the survival of both humans and wildlife, Hanshue and Derosier agree, it’s imperative that we find a way to share it. The Michigan Wildlife Council facilitates public conversation about how human activity affects wildlife and highlights the critical role that wildlife management plays in the conservation of the state’s natural resources.

“When you change any part of a system, you’re changing the system as a whole, whether you realize it or not,” said Matt Pedigo, Michigan Wildlife Council chair. “Sometimes it takes years to see those effects, and it’s almost impossible to gauge, especially in the short term, how those changes will play out over time.”

In Michigan, management of the state’s wildlife and natural resources is primarily funded through purchases of hunting and fishing licenses and equipment – not state taxes. That means that even if you don’t hunt or fish, you’re still able to enjoy the benefits of these conservation efforts, which are already showing progress.

“This mini-plan has been in effect for only a few years, but the larger plan that it’s based on has already seen significant improvements in some of these target species thanks to collaborative efforts,”” Pedigo said. “And when wildlife in an area improves, it has a resonating positive effect on the system overall.”

The plan outlines certain areas that need to be addressed, such as contaminated sediments, poor water quality and unintended introduction of non-native species. Additionally, the U.S. and Canada have pledged cooperation to restore Great Lakes connecting channels under the terms of the 2012 Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. That, combined with the goals behind the proposed Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, introduced by U.S. Rep. Debbie Dingell, makes for a sparkling future for the St. Clair-Detroit River system.

“My greatest hope is at the end of this 10 years to look and say, ‘We’ve met these goals, let’s move on,’” Derosier said. “If we haven’t met them, then we’ll need to reassess and focus our collective efforts to prioritize where we can have the most impact. I’d love to have a better understanding of not only these five species, but of the system as a whole. It’s all there in the plan. It’s just a matter of sticking to it.”

About the Wildlife Action Plan

The baseline plan came together in 2005, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service required every state to create its own plan to be eligible for federal wildlife grant funding targeted at species in greatest need of conservation. That plan ran through 2015, after which the second (current) one was developed, culminating in 2025. These plans are subsequently part of a larger network of strategies across the U.S. that address particular needs regarding water and air quality, species number declines and more. Knitted together they provide a national conservation strategy for conserving fish and wildlife and their habitats.

The five species highlighted in the St. Clair-Detroit River system that part of Michigan’s Wildlife Action Plan are:

Northern Madtom (Noturus stigmosus)

Status: State Endangered

This small member of the catfish family can be found in small to large rivers with moderate to strong currents and substrates of sand, gravel or rock. The northern madtom is nocturnal and avoids shallow waters during the day. There are only three known populations of northern madtom in Michigan, and they are rare or critically imperiled throughout their range.

Mooneye (Hiodon tergisus)

Status: State Threatened

The mooneye is a silvery fish with a small, upturned mouth and distinct large gold-colored eyes. Although historically found in lakes Michigan and Huron, recent accounts suggest that mooneye persist only in the St. Clair-Detroit River system. Only two populations of mooneye are known to exist in Michigan.

Pugnose Minnow (Opsopoeodus emiliae)

Status: State Endangered

The pugnose is a small, silvery minnow with a distinct black stripe running from the eye to the tail. As its name implies, it has a bluntly rounded head and small upturned mouth. Adult pugnose minnows average 2 inches in length. There are three or fewer known populations in Michigan.

Mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus)

Status: Species of Special Concern

The mudpuppy is Michigan’s largest salamander, reaching lengths up to 15 inches. They make squeaky vocalizations that sound like a dog’s bark. Unlike other salamanders, the mudpuppy is aquatic for the entirety of its life cycle and is easily identified by its external bushy reddish gills visible behind its head. Mudpuppies are found throughout the state in rivers, inland lakes and Great Lakes bays and shoal areas. Largely nocturnal, mudpuppies are found under the cover of rocks and logs or other suitable structures. Populations appear to be declining; anecdotal accounts suggest the species has become rare or absent in locations where it was once common in the 1970s and ’80s.

Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens)

Status: State Threatened

The lake sturgeon is Michigan’s largest fish species and is often referred to as a living fossil. Lake sturgeon can exceed 6 feet in length and weigh over 200 pounds. Lake sturgeon have five rows of bony plates along the body, a relatively long snout with four whisker-looking barbels and a shark-like tail. The preferred habitats for lake sturgeon include Great Lakes nearshore areas and large shallow lakes and rivers. They feed in shallows that provide abundant prey, and their spawning habitats include gravel-cobble shoals and large rubble in rivers. Throughout the Great Lakes basin, lake sturgeon are at less than 1 percent of their historical abundance. Currently there are 24 lake sturgeon populations in Michigan, including in the St. Clair-Detroit River system, where there are an estimated 20,000 individuals.